Your Camera- A Tool, Not A Jewel

By Arthur H. Bleich–

For those of you who are not professionals and take pictures for the love of it, technology is your most formidable opponent. Digital cameras have far too many features for you to become comfortable with, especially if you don’t (and I know you don’t) shoot a couple of hundred pictures a day. Film cameras, on the other hand, had relatively few features which made it very easy to take pictures instead of wasting time on button pressing and menu diving.

I met Marc Riboud, the now-legendary French photojournalist, years ago when both of us were shooting in the small Arctic village of Kotzebue, Alaska. We were on assignment for different magazines and we each had state-of-the-art film cameras. But both of us had turned them into virtual point-and-shoots so we could concentrate on capturing the images we needed. We were shooting Tri-X, a black and white film that would be push-processed to an ASA (ISO) of 1200. And yes, some pictures would be grainy, but the resulting smaller apertures and/or higher shutter speeds meant they’d be in focus and not blurred.

We pre-set distances on the focusing ring so that everything that needed to be sharp would be– without us having to waste time constantly turning the ring to focus (remember, no auto-focus then). We’d take a light meter reading (no auto-exposure, either) and then manually bracket exposures under difficult lighting conditions. We essentially cut the amount of fiddling around with camera controls to a minimum so we could concentrate on our picture making, and the resulting images showed it.

The point of this reminiscence is to encourage you to look at your camera the same way you’d look at a hammer. It’s just a tool, the picture’s the thing. As the saying goes: “You have to break a few eggs to make an omelet.” Professionals have a great deal of respect for their cameras; nevertheless if a few dings are required to get the shot, well, you can always buy another camera, but if you lose a great picture, it’s gone forever.

When the front element of his expensive lenses sometimes frosted up, Riboud would impatiently wipe them off with a leather-gloved finger so he could get his picture. The glass looked like it had had been acid-etched with a spider web. At the time, that was a bit much for me, and I protested but Riboud laughed: “Makes no difference, I got the picture. The scratches don’t show.”

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with having a jewel-of-a-camera if you take control of it and not the other way around. To begin with, set it to “Program” and shoot away. Over 95% of your pictures will come out just fine in this semi-automatic mode. Then, hike up the ISO, noise be damned. You’ll be able to shoot at higher shutter speeds to stop more action and get images with greater depth of field. And guess what? You’ll never notice the artifacts unless you blow your pictures up to some insane size which you can’t do anyway with the printer you own.

Finally, take your camera out in bad weather to capture some unusual images. Most photographers never use their cameras in rain, snow or dust so you’ll be able to come back with pictures they’d never get. Remember, the more beat-up your camera looks, the more you’ve been using it as the right tool to get the right stuff. Carry it around with pride. It shows you’re serious about photography.

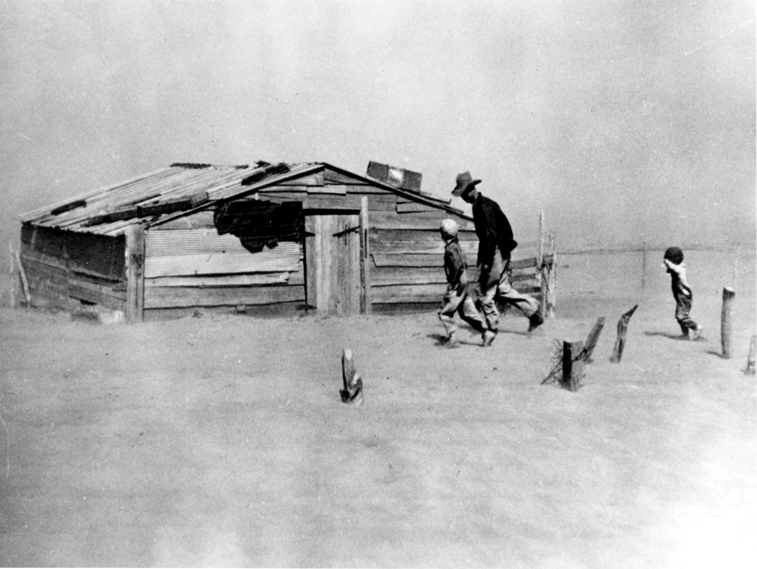

If Arthur Rothstein had worried about ruining his camera, this iconic image of a 1936 killer dust bowl storm in Oklahoma might never have been taken. Library of Congress Photo.

Original Publication Date: December 23, 2013

Article Last updated: December 23, 2013

Comments are closed.

Categories

About Photographers

Announcements

Back to Basics

Books and Videos

Cards and Calendars

Commentary

Contests

Displaying Images

Editing for Print

Events

Favorite Photo Locations

Featured Software

Free Stuff

Handy Hardware

How-To-Do-It

Imaging

Inks and Papers

Marketing Images

Monitors

Odds and Ends

Photo Gear and Services

Photo History

Photography

Printer Reviews

Printing

Printing Project Ideas

Red River Paper

Red River Paper Pro

RRP Newsletters

RRP Products

Scanners and Scanning

Success on Paper

Techniques

Techniques

Tips and Tricks

Webinars

Words from the Web

Workshops and Exhibits

all

Archives

March, 2024

February, 2024

January, 2024

December, 2023

November, 2023

October, 2023

September, 2023

August, 2023

May, 2023

more archive dates

archive article list